'Dogville' and the Practicality of the City Beautiful Movement

What is the ideal city and can it be attained?

Dogville is a fictional small town in America from a film of the same name. The community is surrounded by the Rocky Mountains. The people of Dogville are explained as kind and simple folk by the film’s narrator. They do not earn high wages and their homes are described as glorified shacks, but they make the most of their situation. One of the town’s residents, Tom Edison Jr., is an aspiring writer and philosopher. He sees Dogville as a town of potential. Routinely, he presents strategies at town hall meetings to address a possible “moral rearmament.” He tells his childhood friend, Bill, “There is a lot that this country has forgotten.”1 Tom believes that the only way his fellow people of Dogville will listen to his preachings is through an “illustration,” a social experiment of sorts that would be used as an example of what a perfect version of Dogville would look like.

The City Beautiful movement

In North America between the 1890s and the 1900s, urban planners had similar philosophies, which turned into the City Beautiful movement. The movement had the intent of introducing beautification and monumental grandeur in cities. The beauty of the city would then, in turn, “give us a sense of well-being and satisfaction and a certain unconscious pride in the street.”2 Many of the critics at the time said that the City Beautiful movement was simply a plan built upon an illusion and that there could never be a perfect city. Dogville, in the film, failed under these same pretenses. In this essay, I will be comparing the City Beautiful movement and Dogville to question if a perfect city is feasible and can man-made symbols or “illustrations” get us there.

One of the main plans that were emblematic of the City Beautiful movement was “The White City,” which was presented at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. One of the planners behind the project was Daniel H. Burnham, who was an influential figure in the movement. “The White City” was what Burnham’s team believed a city should be: symmetrical, balanced, and with splendid buildings.3 Historian William H. Wilson documented the impact of Burnham’s plan, named Plan of Chicago, written in 1909. He said the plan was a maturation of the City Beautiful movement.

What critics were most receptive to was Burnham’s proposal of a metropolitan district which spanned a 60-mile radius from Chicago’s downtown. The system of diagonal and circumference roads was designed to “ease crowd control and congestion.”4 Another plan included a large civic centre with a centrepiece of a huge city hall “with a soaring dome resting upon an elongated drum.”5 Burnham explained his plan by saying the central administration building would be “surmounted by a dome of impressive height, to be seen and felt by people, to whom it should stand as the symbol of civic order and unity.”6 Burnham’s plans were made with the intention of practicality and influence, which were chief tenets of the City Beautiful movement.

The idea for a beautiful city came as a reaction to the urban challenges of the early 20th century, where there was unplanned growth, and cities were “crowded, unhygienic, disorderly, and often lawless.”7 There was an intention behind the City Beautiful movement that wanted to start a city from scratch and avoid the mistakes other cities made in the past. However, the City Beautiful movement had its detractors.

Architect Mario Manieri-Elia called the movement an illusionistic experiment and “persuasive in direct proportion to the improbability of their execution.”8 The movement was also criticized for being only for the financially well-off in the city. The emphasis on high art and monuments may prove to be too costly for the layman audience the movement was trying to influence. As taxpayers, the laymen in cities were also not fond of the movement because of how expensive it was to develop these grand schemes.9

It was believed that the movement was largely dismissive of a city’s real problems. Columbia University Professor George B. Ford said in 1911 that the plans set by the City Beautiful movement should not be advanced “before the problems of living, work and play have been solved.”10 Many of the City Beautiful movement’s criticisms fell under an opposing philosophy called the City Practical movement. In an annual meeting for the American Institute of Architects in 1909, Cass Gilbert said that a city practical is “a city that is done, completed, a city sane and sensible that can be lived in comfortably. If it is to be a city beautiful, it will need to be done naturally.”11

The town of Dogville

Dogville, in the film, is described by a narrator as having one road running through the community called Elm Street. The street is lined with houses occupied by the town’s locals, whom the audience gets to meet throughout the film. The houses are described as shacks, and everyone in town earns low wages. Their only exported good is glassware, with the edges ground off to make it look more expensive to sell. Formal elements in the film when presenting this town include drawn outlines of the houses on a sound stage (Figure 1) and the film being broken up into ten chapters, including a prologue with the narrator. These formal decisions express how the film provides a structured outline of what a typical small American town may look like. Director Lars von Trier presents individual archetypes instead of analyzing a meticulously detailed case study. The way the chapters and narrator are used make the film feel purposefully written, that every moment of its story has an intent leading to the

finale.

The town resembles the poverty-stricken communities of America in the early 20th century. The notable thing is that Dogville has no leader and no philosophy by which its citizens can live their lives. Tom organizes town meetings routinely, but what he has found is that the townspeople don’t typically listen to him. He says that he wants to provide the town with an “illustration” or an intellectually stimulating lesson on why the town should work better together.

At one town meeting12, Tom confronts his fellow townspeople by saying the snow is never shovelled properly because everyone only looks after their own property. The way the townspeople only look after themselves is not conducive to how the city is laid out, with each home being side by side. One day a woman named Grace stumbles into Dogville after being chased down by a group of gangsters. Tom believes he has received his illustration. If the town were to receive Grace with open arms, then the people of Dogville may learn to act cohesively as a community. The question that arises at this point of the film is not unlike the City Beautiful movement. Is Tom forcing philosophical lessons on a town that does not need them? Since the people of Dogville are relatively poor, do they have the capacity to work on their moral decisions when the real problems in the town are not addressed?

A single social identity

Dogville accepting an immigrant such as Grace into their community is akin to an example James B. LaGrand gives regarding Progressivism. LaGrand presents the example of Jane Addams and a settlement house she started with her friend Ellen Gates Star called Hull House in Chicago in 1889. Hull House offered kindergarten, education classes, and community center activities in an immigrant neighbourhood. Addams said if immigrants were to live in her community cohesively, then the difference in cultural practices would be unhelpful. She believed that there could be a perfect community if residents were homogenized under a single identity.

Addams thought cultural differences led to disorder, and immigrant neighbours would only benefit socially within their own ethnic groups.13 Addams said that Chicago needed a “bridge between European and American experiences,” which would bring “more meaning and sense of relation.”14 Addams saw her immigrant neighbourhoods as social and cultural vacuums where there was no social organization of any kind.

LaGrand identifies the issue with Addams' project by saying there was still segregated community life no matter how hard Addams attempted to form a social “whole.”15 Critics thought of Addam’s social engineering of immigrant cultures as too ambitious when she tried to include all people of different social classes and ethnic groups to share one cultural philosophy. Tom’s plan seems far-fetched in the same way. The people of Dogville have various sets of needs. To neglect solving the problems that the townspeople have and fail to accept their differences, a generalized moral reformation would not hold.

The figurines

When Grace first gets her tour around Dogville, she comes across the town’s store with seven figurines on the windowsill (Figure 2). Tom, who does not look at the other townspeople as morally favourable, says the figurines say a lot about how awful they are because the shop owners sell them for a price the residents can never afford. Grace provides a more charitable interpretation by saying the figurines cast the town in a different light and characterize the town as “a place where people have hopes and dreams, even under the hardest conditions.”16

The figurines act as a motif throughout the film that reminds the viewer that there may be goodness within Dogville that is bound to be unlocked. Comparing it to the City Beautiful movement, the figurines are also a symbol found within the heart of the town as they stand on the store’s windowsill. For a town that is impoverished and lives in shacks, the artistry of the figurines expresses a beauty that is not found anywhere else. The mere presence of such an item can cast the entire town in a different light. A work of art can spur a community to act in unity. Grace soon gets put to work helping the townspeople with daily tasks and uses her financial earnings to purchase the six figurines one by one. The figurines then take on symbolism for community codependency, that cohesively providing help within the community leads to these symbols being owned and coveted.

The vices of mankind

Later in the film, the people of Dogville start taking advantage of Grace and her labour. She starts working longer hours and then continually spirals into sexual exploitation. At one point, one of the townspeople, Vera, catches her husband, Chuck, being intimate with Grace. Vera decides to smash all her figurines to punish Grace for allegedly seducing her husband.17 The gift that Grace once gave Dogville, that her presence may create a united community, is squandered in this scene. Grace saw the hope for Dogville in these figurines. Akin to the art and monuments found in the City Beautiful movement, the figurines provided Grace with the hope that Dogville may see a better future. However, the town is rooted in depravity. Tom’s illustration does not correct the attitudes of the townspeople but rather provides them with a hollow illusion of what a perfect town would look like.

Some of the most notable problematic citizens of Dogville include Chuck and Jack. Their stories and guilts shed light on how Tom’s illustration neglected to ease their pain. Chuck was once like Grace. He immigrated from the city in search of a better life. Chuck says, “l found out that people are the same all over. Greedy as animals. In a small town, they're just a bit less successful.”18 Chuck looks down on Grace because he once had the same hope for Dogville. He knows that the hope is an illusion and that a moral lesson would not change the deep-rooted vices of mankind or the townspeople.

Jack is a blind man but refuses to admit it. When he first meets Grace, he recounts a time when the sun shone into Dogville’s town store on the O in the “open” sign, meaning it was time for an evening purchase. Grace tells Jack: “l think we've talked long enough about the way we remember seeing things. Don't you? Why don't we talk about something that we can see right now?”19 Grace then pulls a heavily fortified curtain (Figure 3) away from a window in Jack’s house to reveal a beautiful view of a neighbouring gorge.

Jack admits that he once was able to see the beautiful view but is now blind and sees Dogville as a “wretched town” with nothing to see. Jack’s blindness and the curtain covering up the beautiful view are examples of why Dogville may never be able to be the perfect town and live up to its potential. The townspeople are poor. Beauty and high art may not be accessible immediately because they are frustrated with their own guilt. Jack does not want to admit he is blind to others because he sees it as his own problem with no solution that his neighbours or Tom’s illustration can provide.

“Perfect” not attainable

The film ends with Dogville being burned down and its citizens being shot at the hands of Grace’s father, who is a gangster. She concludes that even under the town’s circumstances of poverty, she would not have committed the same vices that the people performed against her. She agrees that her father should commit this act of justice. Tom, at the end of his life, agrees that Grace’s illustration was far more insightful than his, and he was wrong for projecting his idea of a perfect town on a community that needed support in different ways.20

This ending feels sudden and unsympathetic but returns to the idea that the film is an outline rather than a real explanation of how cities or towns should be governed. Dogville is as much an illustration as Tom’s. They both have flaws in their storytelling. As the director, von Trier believes that the film does not provide answers as well. The last line of the movie asks the viewer if the attitudes of Dogville will haunt Grace for the rest of her life, and admits that we will never get that answer. The City Beautiful movement was not a plan with a desired ending. It was a hope that perfect could be attained. Many critics of the movement found this unfeasible, the same feeling Grace felt when she burned down the town.

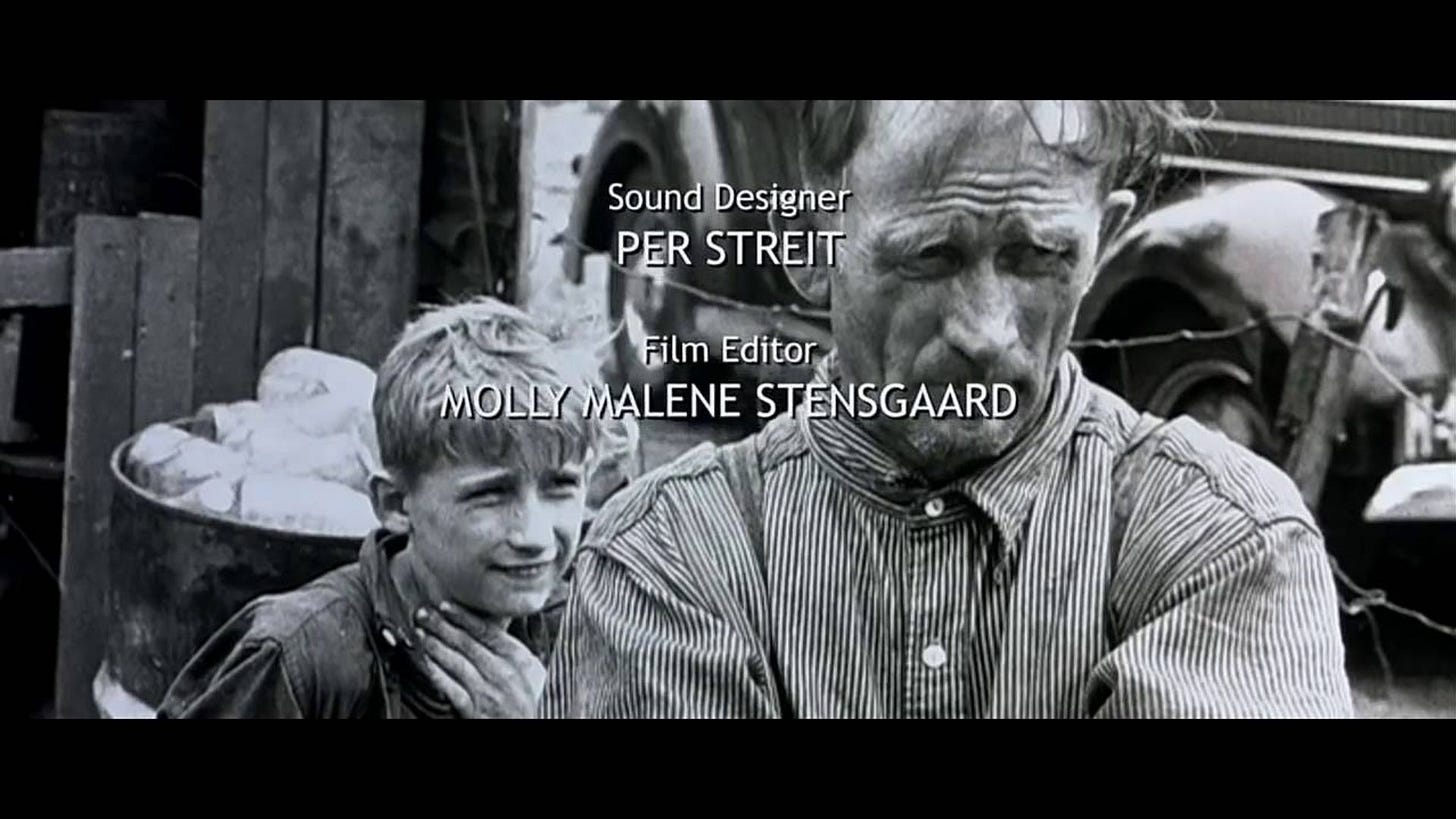

The ideas of America’s poverty and the perfect city become even more realized during the film’s closing credits. The credits roll alongside a series of documentary photos of poverty-stricken Americans from Jacob Holdt's American Pictures, accompanied by the song "Young Americans" by David Bowie (Figure 4). It places von Trier’s outlandish film into context. Von Trier is not American, nor is David Bowie. Von Trier is giving his impression of America as a Danish filmmaker. He sees the country as a place with economically underprivileged citizens and creates a film to tell their stories. It is not a story that is deeply political because that would be ignorant of someone without that expertise, but instead, it is a framework about how people should treat each other on a fundamental level.

Those feelings are compared to Bowie’s song about his own impressions of America. To quickly summarize Bowie’s intentions behind the song, he presents the accepted narrative that America is a country of hope in its capitalistic splendour. However, he slowly begins to tear away at that perfect image. Burnham, during the Beautiful City movement and Addams’ project at Hull House, attempted to capture a perfect America, a mission that their critics say is too ambitious of a venture, that is, if it is attainable at all.

My essay uses art to explain cities in many ways. I talked about a movement that uses monuments to spur a community’s unity. I talked about a film and a song that attempted to critique the possibility of a perfect city, town, or country. Ultimately, it might just be the case that art is the only medium in which perfect unity can be attained. Art allows a storyteller to dream and create these idealized worlds that may be unobtainable in reality. Taking a fictional premise and interpolating it into urban planning may be a hopeless venture. My essay attempted to reach the boundaries of that possibility.

Dogville leaves viewers with questions to consider. My essay, being its own art form, poses those same questions and hopefully creates more. Looking back at history and these different movements, then fast-forwarding to von Trier’s American overview, shows that the conversation about the perfect city is still ongoing, possibly with no end in sight.

How social media might build a city beautiful

Jordi Oliveras, in his article named An Urban Odyssey, provides an outlook for conversations on perfect cities leading into the future. Individuals online have more firsthand experience of a city’s beauty than ever before while using social media.21 Citizens who experience the advantages and disadvantages of their city can share that information with the world. Websites such as Yelp or Google reviews have users critiquing every facet of a city in ways that were never possible before.

Online reviews expose faults of certain establishments and, over time, create a repository of what would be considered a “perfect” destination. Hypothetically, using this information creates an idealized city. Different establishments, organizations, and even countries are regularly compared and ranked in magazines, influencing tourism and lifestyle. Applications like Google Earth and Maps offer an opportunity to travel and form our own opinions from the comfort of our own homes. We can be a part of another country’s conversation on “perfection” without even being a local. When someone likes your vacation photos on Instagram, they very well might have just made a claim that the location you vacationed in was favourable.

City builder video games such as SimCity and Civilization are born out of our desire to take the idea of city perfection into our own hands. We innately believe we have the ideal city pictured in our minds. When we vote for our political leaders, we hope that their ideal city is close enough to ours so they can hopefully carry out our desires. It may very well be the case that a perfect city is never going to be feasible because there will always be pushback and a variety of opinions when given the choice to lead a populace.

It may still be too early to quantify how social media interactions can create a city beautiful. It is also unclear if a city beautiful could actually unify a city. There is no knowing if a community can be morally affected by urban planning, especially when other important issues are not addressed. However, it remains clear that a city’s image has never been more important now in the information age. A statue or a work of art that signifies a national symbol has never been so easy to share worldwide. With new technologies and ways to interact online, it will be interesting to see how city practices continue to be compared and idealized over time.

Dogville (Denmark: Zentropa Entertainments ApS, 2003), https://mubi.com/en/ca/films/dogville, 7:40.

William H. Wilson, “The Glory, Destruction, and Meaning of the City Beautiful Movement,” in The City Beautiful Movement (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989), 281–305, 87.

Jordi Oliveras, “An Urban Odyssey: City Beautiful to City Instagrammable,” Architectural Design 93, no. 1 (2023): 46–53, 48.

Wilson, City Beautiful, 68.

Wilson, City Beautiful, 69.

Wilson, City Beautiful, 69.

Oliveras, Architectural Design, 50.

Wilson, City Beautiful, 70.

Wilson, City Beautiful, 76.

Wilson, City Beautiful, 75.

Wilson, City Beautiful, 75.

Dogville, 18:00.

James B. LaGrand, “Understanding Urban Progressivism and the City Beautiful Movement,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 87, no. 1 (2020): 11–21, 15.

LaGrand, Pennsylvania History, 16.

LaGrand, Pennsylvania History, 16.

Dogville, 25:30.

Dogville, 1:40:00.

Dogville, 42:00.

Dogville, 45:00.

Dogville, 2:39:00.

Oliveras, Architectural Design, 52.